Objection #2: “They’re Taking our Jobs!”

Dismantling tribalist fears couched as economic arguments against increased immigration

This post is the third in a series of articles debunking the most common populist arguments against (mostly) open immigration, based on my dozens of interviews on the topic since I began broadcasting The Bob Zadek Show in 2008.

America professes to love the free market and free enterprise. Those terms imply competition. Americans are glued to their TV sets, watching professional sports. We profess to adopt competition in the free market, yet we're scared to death of it. Years ago, I took a live call on the air from a man named Dmitri, who perfectly encapsulated this anxiety:

“We have a huge population of unemployed and under-employed people with lower or marginal skills that could be employed in those jobs that are taken by the low-skilled illegals. I've been in factories and at construction sites where it seems like almost the entire labor force is what I believe to be illegal immigrants. Meanwhile, we have a huge number of citizens that are unemployed and underemployed. Why not let them work at these jobs the illegals are taking?”

As Dmitri’s question illustrates, much of anti-immigrant anger is driven by the fact that immigrants allegedly “take our jobs.” I call it the “my job” mentality. Americans don't want somebody else taking away their job. In other words, they don't want to have to prove that they are the best person to do a job at a particular wage. But if you aren’t the best person to do that job at the best price, then it’s emphatically not your job. Being born in America is not a guarantee that you will have a job. It is only a guarantee that you will have the right to compete on a level playing field for a job.

Certain Americans want to be paid above-market wages in the same way that others want to live in below-market, rent-controlled departments. What is a job, other than simply an un-coerced exchange of labor for money? If you feel that your job is threatened by immigration, it simply means you need to do better at your job. What right do you have to expect zero competition for your job?

The criticism that immigrants reduce native employment is factually unfounded. Instead of being based on sound data, the “my job” mentality is rooted in tribalism. The Cato Institute’s Alex Nowrasteh summarizes the origins of this specious sentiment:

Alex Nowrasteh: [O]pposition to immigration is founded on an appeal to the primitive and tribal elements of our psyches. It's not an intellectual argument. It's fear of the outsiders – fear of the person from the other tribe doing unspeakably bad things to us. If we were talking about immigration as hunter gatherers 10,000 years ago, it wouldn't be about “taking our jobs,” it would be about them killing the mastodon before we got a chance to slaughter it. They've updated the rhetoric, but it still appeals to that primitive part of their of our brains, which is sadly divorced from the economic reality of the modern world.

Alex says he’s never seen an economic model in which more people are not good for the economy as a whole.

Even the most anti-immigrant research done in legitimate, peer-reviewed, academic journals on this topic finds that immigration increases the size of the economy, as well as American wages, by far more than any downside associated with it.

The economic literature explains these benefits in terms of the “complementarity” of immigrant labor with native labor, rather than its “substitutability.” Two identical goods or services are considered substitutes for each other and do indeed compete for dollars. However, pairing complementary skills tends to make everyone richer.

AN: If you're going to compete with immigrants, they have to be very similar to you in terms of education, language ability, experience, etc. Most immigrants have very different levels of experience, different levels of language and ability – so there's not that much competition to begin with.

The number one skill difference is found in English language ability. Lower-skilled immigrants tend to push lower-skilled Americans up the distribution of wages ladder. The best example of this is a restaurant: low-skilled immigrants in restaurants do the jobs that don't require communication with the customers. They are the busboys. They work in the kitchen. They are the janitors. The low-skilled Americans are the waiters and waitresses. 30 years ago, those unskilled Americans would be washing dishes. Now they're serving customers and making a lot more money.

Remarkably, even if you look at areas of the labor market where you would expect to see a lot of competition between Americans and immigrants, you see job increases. The evidence on wages is mixed, but the estimates show a very small positive net effect of somewhere around 1% or less.

One might expect more competition for jobs to lower wages of Americans, yet instead we see the countervailing supply and demand forces more than making up for the slight reduction in wages.

On the supply side of the economy, immigrants make it possible for more things to be built, because they are workers and entrepreneurs and inventors and investors. They also increase the demand side of the economy as consumers. They buy things from Americans like real estate, and rent houses.

We hear the same fallacy of zero-sum thinking – mostly from the economic left – when they speak as if there is a fixed supply of resources, that needs to be “redistributed” because there’s only so much to go around. No, says Alex:

There is not a fixed supply of jobs.

There’s not a fixed supply of the types of work that people can do.

These things can change. Having more people here helps growth, increases jobs, and increases wages in the long run for most Americans.

Winners and Losers

When we talk about the benefits to most Americans, that implies that there are some who do not benefit, or do not benefit as much as others.

To give an honest answer to Dmitri’s question, we can’t ignore the economic facts of life, because there are in fact winners and losers.

AN: There are certain jobs where wages have gone down due to immigration, such as working in agriculture. But we've seen Americans move out of those industries into more highly-paid industries, largely because of immigrants taking those jobs at the bottom and pushing them up.

There are three areas where economists broadly agree in the entire economics profession. One is that free trade is good. Another is that price controls are bad. The third is that immigration is good for the economy. The only disagreement is how good and who benefits the most. So when you hear people talk about immigrants taking American jobs and lowering wages for Americans, the economists who have spent decades studying this question have found no evidence of this occurring, with some very minor exceptions that affect very few people.

Immigrants make up about 13.5% of the U.S. population and are about 16% of the workforce. They are more likely to work than native born Americans are, and they boost our GDP by somewhere around 12–15% based on the estimates. They get most of the benefits of that because they are the ones who are adding to our production.

Nobody disagrees with anything that I have said right now. The only point of disagreement is the effect on wages of native born Americans by having these immigrants who are here working. One economist from Harvard University named George Borjas – the most skeptical economist on the benefits of immigration – found that roughly 30 million immigrants from 1990 to 2010 who came to the US lowered wages of native high school dropouts by about 1.7%, but raised the wages of every other American by about 1% overall.

On the other side of this are the economists Giovanni Peri and Gianmarco Ottaviano, and they find that over that entire time period, immigrants raised the wages of native-born Americans by about 0.6%. So, we are basically talking about very small differences on wages, but overall increases for the vast majority of Americans. The most negative finding in the entire academic peer-reviewed literature is that immigration over the last 20 years has lowered the wages of high school dropout natives by about 1.7%. However, it is outweighed even in that research by the weighted benefits to other native born Americans who have at least a high school degree or above.

The negative effect on wages only falls on a small cohort of the working population, which is native-born males with a sub-high-school education, a group that makes up only 9% of the population. So, in truth, a small cohort of the working population is negatively affected, only to a minuscule extent. However, there are many factors that reduce the wages of that particular cohort of the working population. Automation has been doing that for decades. Movement of capital and globalization reduces wages for uneducated Americans. Yet all of these trends that harm one narrow group on one dimension (employment) benefit society profoundly as a whole. If we selectively oppose immigration, why not also oppose all the other labor-saving devices and phenomena that happen in society? Should we have opposed the invention of automatic elevators because of the effect on elevator operators without a high school diploma?

Why aren’t we railing against efficiency? Efficiency destroys jobs as well, but efficiency is good for all of us, even if some people will suffer temporarily. It makes no rational sense to focus on the effect to one small group, even though the overall effect is positive.

We’re All Winners: Why Wages Rise

The conditioning of tribalism combined with zero-sum thinking is powerful. It’s one thing to cite the economic research from across the political spectrum as evidence that immigration doesn’t take away American jobs, but it’s another thing to actually understand the economic dynamics that link immigration with higher wages and more jobs. For this, we need to put on our economist hats and do some real thinking.

AN: Wages for people are determined by their productivity, i.e., how much stuff you can make for your company. If I can produce a maximum of $15 of revenue for my firm then I cannot be paid more than $15 because otherwise the company would be losing money and would fire me. The company wants to pay me less than that, but because I’m a worker who wants to make money, I can always go to another company that will pay a little bit more, because I can produce $15. From this supply and demand interaction, we get workers being paid for what they are worth.

Workers also need tools – capital – in order to be productive. Productivity and wages are ultimately determined by the supply of workers and the supply of these capital goods. In the short run, more immigration lowers the price of labor. However, it also increases profits and investment in new capital.

Businesses and others take advantage of this lower price of labor in the short run, but then make more and more investments in capital because the profits from owning capital increase. Wages might slightly fall in the short run, but they rise again as businesses build more capital to take advantage of the lower labor costs. Since capital now has a higher return on investment, you get an increased supply of capital, which raises productivity, which [in turn] raises wages.

Investors and businesses are not stupid. They anticipate higher wages. You don’t even typically get that short-run decline because businesses and the economy anticipate a million or so immigrants coming in every year to work. They make those investments in capital in advance before they even arrive.

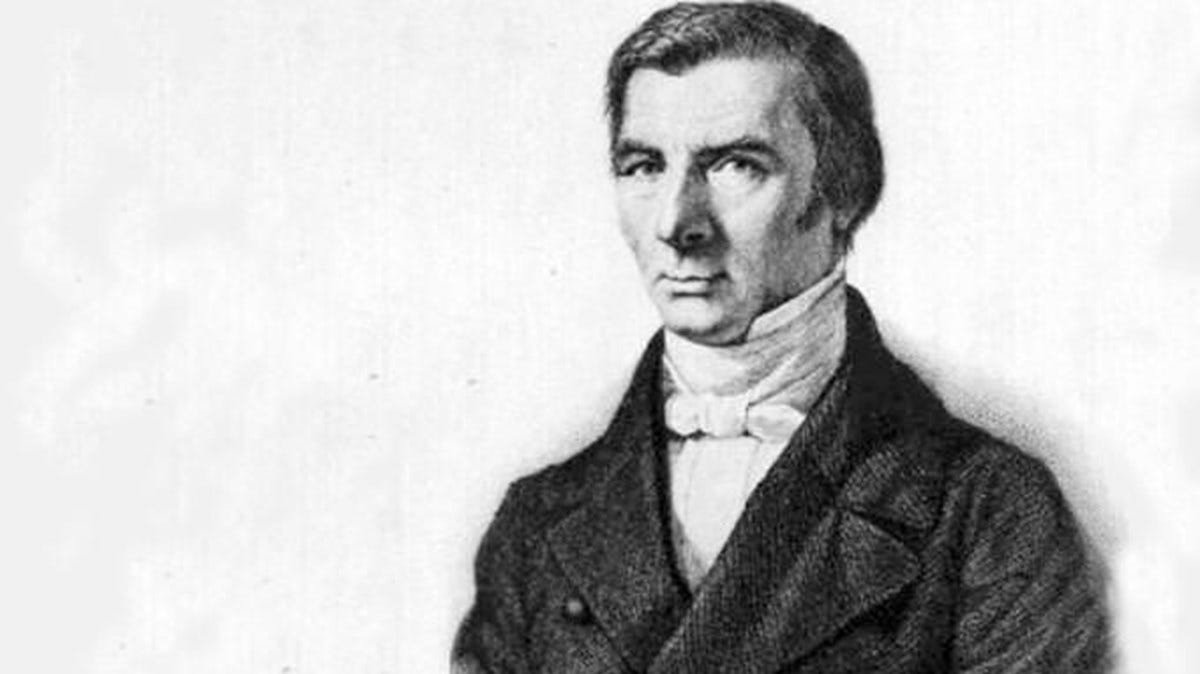

Seen vs. Unseen Reduction in Wealth

Frederic Bastiat, an economic philosopher from the mid-19th century, observed that often the small benefits are seen and visible, while profound detriments are dispersed and invisible. When you go to the supermarket and find that the produce you buy is a bit more expensive, you're not going to say “Darn, immigration policy – now my apples are four cents more expensive!”

The effect is invisible to you, although the overall effect on the economy is enormous. On the other hand, the small segment of the population who gets a raise or gets a job because of a more restrictive immigration policy will notice and will say, “Thank goodness – now I am making $35 a week more!”

Meanwhile, the overwhelming majority of the population, which is paying through the higher cost of goods, will not know that it's a result of the restrictive immigration policy.

Nowrasteh points out another unseen effect – that many businesses would see their customer bases deported under a strict immigration policy.

AN: There is no path to prosperity by decreasing the supply of people in the country. it diminishes both the supply and demand sides of the economy. Short term, it makes almost all of us just a little bit poorer, and in the long run, it makes all of us poor.

The economic history of our country shows that economic life accelerates during periods of liberal immigration policy, and we either flatline or are worse off during periods of constricted economic immigration policy.

Addressing the Shortage of High-Skilled Workers

When I interviewed Daniel DiMartino, he was getting his PhD from Columbia University in New York. DiMartino is from Venezuela, where his skills as an economist are sorely needed by the socialist rulers yet completely under-appreciated. DiMartino points out how irrational our bureaucratic and sluggish immigration system is when it comes to depriving our workforce of the class of high-skilled workers which stands to benefit us the most.

Daniel Di Martino: In the area of high-skilled immigration, the United States has fallen behind most other developed countries. If you are somebody who has a PhD in a STEM (Science, Technology, Engineering and Math) area, or if you are a corporate executive, or if you have a lot of money to invest and create jobs in the United States, it is so much harder to immigrate to this country then say to Canada, the United Kingdom, Australia, New Zealand or any of the other developed countries in the Anglosphere.

This has resulted in a loss of jobs for Americans. That has resulted in lower wages for middle-income Americans. That has also resulted in less innovation, less entrepreneurship, and a less dynamic United States.

Even if an American citizen marries an immigrant, there is a long bureaucratic process to obtain citizenship for your spouse. Not only does the bureaucracy cost money, but it hurts the economy by creating uncertainty and robbing high-skilled workers of their prime years of productivity.

Immigrants are the Ultimate Entrepreneurs

Immigrants during the Ellis Island period were the ultimate entrepreneurs. An entrepreneur is somebody who risks their own capital – indeed, their own life – betting on their ability to succeed. Entrepreneurs are like the quarterback in football: they are out there by themselves, with very little support. When they mess up, they go down, and when they succeed, they get the glory.

Entrepreneurs start with an idea for a business. Then they “bet the ranch” and they either succeed or fail. How can one bet more than leaving your home country, where you speak the native language, and going to a foreign country with no support whatsoever, knowing full well that your ability to feed your children will depend only on your own guile, skill, and commitment to work? If we had more people willing to do this, the fiber and economic health of our country would be much stronger. We desperately need immigrants. We should not be denying them access but rather welcoming them to this country.

Beyond that, who comes here is not a random lottery. There is a self-selection process: those who make the decision to leave poverty or economic immobility come here because they want their kids and grandkids to have more than they have. They're not coming here to take; they're coming here to give. This is not just a hunch or stereotype, it’s borne out in the statistics:

AN: Immigrants are more than twice as likely as native born Americans to start a company. That's compared to Americans who are, on average, some of the most entrepreneurial people around the world.

One of the best examples is in Silicon Valley – over half of the startups in Silicon Valley as late as just a few years ago were started by immigrants, with Indians dominating that trend. One third of semiconductor startups were founded by immigrants – 32% of computers and communications, and 28% of all software firms.

However, it’s not just in high-skilled tech jobs where immigrant founders are disproportionally represented. I grew up in Queens, where jitneys were once a regular mode of transportation. They would pull up in the rain, as passengers were lined up huddled with umbrellas, waiting for a bus, and they would take you almost door-to-door for the same cost of a bus fare to Manhattan. The jitneys were for the most part driven by newly-arrived immigrants – mostly Central Americans, like Ecuadorians and Nicaraguans. They were safe and insured, and you would feel comfortable putting your loved ones in these jitneys. Many of the customers were the very same Ecuadorians and Nicaraguans (and now Nigerians) who were ill-served by public transit. These immigrants, who just wanted to earn a living, started to build capital for their families and help other immigrants get to work.

Nowrasteh cites more statistics on small businesses in New York City, where 36% of the population in New York City is foreign-born, but where 48% of all the small businesses are started and owned by immigrants – everything from restaurants, to dry cleaners, to construction contractors, to every imaginable form of transportation.

All of these entrepreneurs risked everything to come to this country.

AN: Immigration is a great filtering mechanism for finding the people who really want to make something of the opportunity to come here. That has always been the case.

Who Opposes Competition?

Of course, no good deed goes unpunished, and the jitney drivers of the outlying boroughs soon became the target of the Transport Workers Union.

Throughout his career as a lawyer and litigator for the Institute for Justice, Bob McNamara has fought against anti-competitive laws passed through lobbying efforts by the competition itself. McNamara’s clients are overwhelmingly underdogs against much deeper-pocketed special interests, who seek to preserve monopoly status against upstart immigrants and undercapitalized entrepreneurs of all stripes. To make matters worse, the competition rarely actually stands to lose market share to the new competition. Was the New York City subway system fearful of being put out of business by the Jitney drivers?

Bob McNamara: This is the attitude you see time and time again from these politically-favored businesses who end up on the other side of these fights. It's not that they're going to be destroyed by competition. It's just a natural impulse, once people get the idea that they can use government to shut down their competition, that every dollar counts. The same impulse that makes entrepreneurs work harder in a free market – to get every last customer in the door and make every sale they can – gets turned on its head as soon as people realize they can achieve the same end by going to government and getting special favors. Then, every dollar counts in the other way. You have to put every competitor you can out of business, and get every regulation imposed that prevents the other guy from earning an honest living.

The “dollar vans” (aka jitney transports) we're never going to destroy the city buses. But nonetheless, unions got rules passed that made it illegal, for example, for a dollar van to drive down any street in New York City where a city bus ever drove. Even if the city bus line only went down a street at 3 AM every Tuesday and never came back, that street was off-limits to dollar vans 24 hours a day. Too bad for the people who had the misfortune to live on that street!

The jitney operators were helping get people to work for a fair price, and doing so honestly and safely. Just imagine if you were a dry cleaner, and you could go to court or tell City Council, “I have this uncomfortable competition from another dry cleaner down the block, please make their business illegal, so I can then be free of competition.”

That is what goes on in these transportation businesses that run to the government to protect them from the immigrant-run competition. Just imagine a professional sports team getting their competition declared illegal, saying, “You can't weigh more than 275 pounds and play football.”

There's nothing less American than that.

The War on Chinese Restaurants

Bizarrely, it is conservatives – who usually espouse the virtues of free market competition – that wish to stifle the free market in their immigration policies. Anti-competitive laws are nothing new, of course. Business people have tried to shut down their competition for as long as economies have existed. Gabriel Chin, author of The ‘War’ Against Chinese Restaurants, highlights one particularly ugly chapter in our history around the end of the 19th century. If it weren't so sinister, America’s war on “sweet and sour pork” would appear a bit silly. What group comprised the frontline fighters against upstart Chinese restaurateurs? You guessed it – the unions:

Gabriel Chin: The main group that opposed Chinese restaurants in this period was the cooks and waiters union, and later the hotel employee and restaurant employees union, which was part of the American Federation of Labor. White restaurant workers and owners saw that these Chinese restaurants were taking their business and didn’t want to compete against them. Chinese restaurants were inexpensive and delicious, so the unions thought this problem had to be stamped out.

Only a union could see delicious, cheap take-out food as a problem that had to be stamped out. But they found ample support in the baser, tribalistic segments of the population. The Chinese looked different, which was undoubtedly a factor. After all, there wasn't a war on Italian restaurants:

GC: Any number of immigrants from Germany or Sweden or Italy or Ireland could come to the United States. So it wasn't immigration competition that they were concerned about, per se. It was a race thing.

First, the unions asked their members and all other members of the community to boycott Chinese restaurants and imposed fines on their members when they broke the boycott. Then they started picketing in front of restaurants and heckling the customers who came in and out. Much to his credit, a judge in Cleveland Ohio issued an injunction against those who physically blocked people from entering restaurants, writing that “the law of competition in business controls business relations as immutably as the law of gravitation controls matter. If a Chinaman can furnish better food at less cost than a white man, he will be patronized and I know of no law that will compel or force any patron to pay a higher price for inferior food, merely because it is prepared and served by a white man.”

What beautiful language!

In the end, the unions lost their “War Against Chinese Restaurants,” as evidenced by any simple search for Szechuan food on Yelp!

However, the Chinese Exclusion Act represented a major victory for the unions, and you can read the full saga in Chin’s research article of the same name, which details union attempts to block competition in the name of health and safety regulations, licensing schemes, and other thinly-veiled rationales for the same old prejudices.

The short version of the story is that the American Constitution and federalist system prevailed: in the end, industrious Chinese restaurateurs found the jurisdictions that allowed them to work and earn a living.

Today, workers continue to gravitate to the countries that welcome them, providing benefits to the native population as they earn a living for themselves. America has a choice to either resume its position as the leader in accepting and naturalizing the ultimate entrepreneurs from around the world, or else settle for a second-rate economy. Of course, as we saw in the previous chapter, immigration is regulated at the Federal level, and states can only do so much to welcome immigrants. Later installments of this series will take up the question of how states can push back against overly restrictive federal policy, but next we must turn our attention to perhaps the most common objection to immigration of all – that immigrants come here to abuse our welfare system. Stay tuned…